The LATERAL keyword can precede a sub-SELECT FROM item. You will encounter this style of abbreviating quite frequently.Since PostgreSQL 9.3 we have a new LATERAL option for FROM-clause subqueries and function calls.Īccording to the documentation what it does is: You can also use these kinds of aliases in other queries to save some typing, e.g.:įROM weather w JOIN cities c ON w.city = c.name Here we have relabeled the weather table as w1 and w2 to be able to distinguish the left and right side of the join. Hayward | 37 | 54 | San Francisco | 46 | 50 San Francisco | 43 | 57 | San Francisco | 46 | 50 W2.city, w2.temp_lo AS low, w2.temp_hi AS high SELECT w1.city, w1.temp_lo AS low, w1.temp_hi AS high, So we need to compare the temp_lo and temp_hi columns of each weather row to the temp_lo and temp_hi columns of all other weather rows. As an example, suppose we wish to find all the weather records that are in the temperature range of other weather records.

#Postgresql cross join full

When outputting a left-table row for which there is no right-table match, empty (null) values are substituted for the right-table columns.Įxercise: There are also right outer joins and full outer joins. This query is called a left outer join because the table mentioned on the left of the join operator will have each of its rows in the output at least once, whereas the table on the right will only have those rows output that match some row of the left table. (The joins we have seen so far are inner joins.) The command looks like this:įROM weather LEFT OUTER JOIN cities ON weather.city = cities.name This kind of query is called an outer join. If no matching row is found we want some “ empty values” to be substituted for the cities table's columns. What we want the query to do is to scan the weather table and for each row to find the matching cities row(s). Now we will figure out how we can get the Hayward records back in. But for a reader of the query, the explicit syntax makes its meaning easier to understand: The join condition is introduced by its own key word whereas previously the condition was mixed into the WHERE clause together with other conditions. The results from this older implicit syntax and the newer explicit JOIN/ ON syntax are identical. The tables are simply listed in the FROM clause, and the comparison expression is added to the WHERE clause.

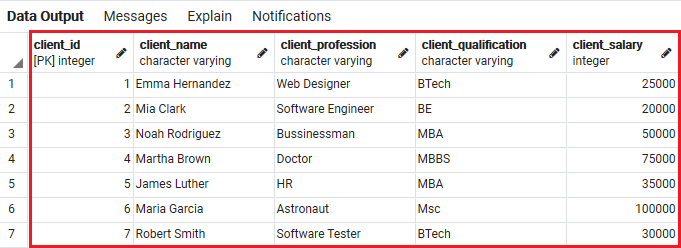

This syntax pre-dates the JOIN/ ON syntax, which was introduced in SQL-92. Join queries of the kind seen thus far can also be written in this form: It is widely considered good style to qualify all column names in a join query, so that the query won't fail if a duplicate column name is later added to one of the tables. Weather.prcp, weather.date, cities.locationįROM weather JOIN cities ON weather.city = cities.name SELECT weather.city, weather.temp_lo, weather.temp_hi, If there were duplicate column names in the two tables you'd need to qualify the column names to show which one you meant, as in: Since the columns all had different names, the parser automatically found which table they belong to. SELECT city, temp_lo, temp_hi, prcp, date, location In practice this is undesirable, though, so you will probably want to list the output columns explicitly rather than using *: This is correct because the lists of columns from the weather and cities tables are concatenated. There are two columns containing the city name. We will see shortly how this can be fixed. This is because there is no matching entry in the cities table for Hayward, so the join ignores the unmatched rows in the weather table. There is no result row for the city of Hayward. SELECT * FROM weather JOIN cities ON city = name Ĭity | temp_lo | temp_hi | prcp | date | name | location

This would be accomplished by the following query: For example, to return all the weather records together with the location of the associated city, the database needs to compare the city column of each row of the weather table with the name column of all rows in the cities table, and select the pairs of rows where these values match. They combine rows from one table with rows from a second table, with an expression specifying which rows are to be paired. Queries that access multiple tables (or multiple instances of the same table) at one time are called join queries. Queries can access multiple tables at once, or access the same table in such a way that multiple rows of the table are being processed at the same time. Thus far, our queries have only accessed one table at a time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)